Q and A with Miche Booz

Q and A with Miche Booz by Beth Herman

Swiss-born and French bred (that's bred, not bread), Miche Booz of Miche Booz Architect spent a peripatetic childhood navigating the neighborhoods of Jordan, Pakistan and Indonesia.

Swiss-born and French bred (that's bred, not bread), Miche Booz of Miche Booz Architect spent a peripatetic childhood navigating the neighborhoods of Jordan, Pakistan and Indonesia.With a developmental economist father (also an admitted closet interior designer who coveted Danish Modern), and writer/ illustrator/ painter mother, Booz grew up in the shadow of iconic architecture like the Taj Mahal and Eiffel Tower, and without television, which left considerable time to cultivate his own artistic DNA. Though the young Miche trained his pencils and brushes on favorite military tanks and boats, as an architect he has turned his attention to painterly (and/or colored pencil) executions of design, much in the manner of Le Corbusier. DCMud spoke with Booz about his art and how he has applied it to his latest project: a 2,000 s.f., 3-bedroom, 2-bath net positive residence scheduled for momentary groundbreaking in Clarksville, Maryland.

DCMud: Why do you draw and paint as opposed to using 21st Century technology?

Booz: I went to art school and got into watercolor, and liked the medium a lot, before I came to architecture at age 32. It's not the only medium I use, though I find it the most evocative and it helps me design and understand things in a more tactile way. There's something that goes on when you actually have a colored pencil or a brush in your hand that connects you to the architecture and helps you work out design solutions.

DCMud: When does technology come into play?

Booz: We're an office of four, and the three others here use it more than I do: AutoCAD and SketchUp. I don't design on the computer at all.

DCMud: So with all that, how did the Clarksville net positive project come into your orbit?

Booz: I've known Ed Gaddy, a solar energy engineer for spacecraft, since 1980. We've had dialogues over the years about doing an energy efficient house. A few years ago he found a 1 1/2-story Cape three minutes' walk from where he works. As an environmentalist, among other things he wanted to walk to work to conserve his carbon footprint.

DCMud: Describe the property.

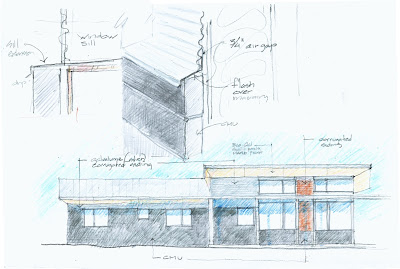

Booz: It's 1.2 acres on a south-facing lot. The existing house was not very energy-efficient, and we determined we could not effectively renovate it into such. There is that truism that the greenest house you build is the one you don't tear down; in this case we'd have had to disassemble it so much it would've been akin to tearing it down. That said, we are actually keeping the first floor deck and the basement underneath for storage, and building a platform with a sculptural, prismatic object that we're putting the solar array on. The house will be built next to it and is a composition of two squares: A public square and a private square. The kitchen/pantry/living area has a taller roof, and then bedrooms and bathrooms are under the lower roof.

Booz: It's 1.2 acres on a south-facing lot. The existing house was not very energy-efficient, and we determined we could not effectively renovate it into such. There is that truism that the greenest house you build is the one you don't tear down; in this case we'd have had to disassemble it so much it would've been akin to tearing it down. That said, we are actually keeping the first floor deck and the basement underneath for storage, and building a platform with a sculptural, prismatic object that we're putting the solar array on. The house will be built next to it and is a composition of two squares: A public square and a private square. The kitchen/pantry/living area has a taller roof, and then bedrooms and bathrooms are under the lower roof.

DCMud: What about the net positive aspect of this house?

Booz: It may be a little tongue-in-cheek, but Ed's special goal is to have the most energy-efficient house in Maryland -- he's going for the trifecta of certifications. He wants to have a Passive House (Passive House Institute U.S., or PHIUS) - a German performance-based certification program whose principles have a long history in the U.S. that addresses air tightness, insulation and energy use. PHIUS is less interested in materials and site strategies than LEED and Living Building Challenge are. But he's also going for LEED Platinum, and for the Living Building Challenge.

DCMud: Rather ambitious objectives. With all of that, how are you going to achieve net positive -- to build a home that produces more energy than it uses?

DCMud: Rather ambitious objectives. With all of that, how are you going to achieve net positive -- to build a home that produces more energy than it uses?Booz: For one thing, we rotated the house directly south, which is one reason for building a new one, for purposes of solar gain. It has architecturally integrated solar panels, and we also have a couple of thermal solar panels on top of a shed behind the house for hot water.

The exterior is concrete block and corrugated metal. The roof is a standing seam Galvalume, and it all sits on a polished concrete slab.

DCMud: Tell us about insulation.

Booz: It's going to use very little energy to heat and cool with highly insulated walls, roof and slab insulation: R-Values are 68, 100 and 38, respectively. In fact the R-Value of the Zola window glazing is 11.1 -- comparable to the R-Value of 3.5-inch thick fiberglass batt that's found in many homes.

Booz: It's going to use very little energy to heat and cool with highly insulated walls, roof and slab insulation: R-Values are 68, 100 and 38, respectively. In fact the R-Value of the Zola window glazing is 11.1 -- comparable to the R-Value of 3.5-inch thick fiberglass batt that's found in many homes.The one thing this house does is avoid thermal bridging, where you have structure or components of the house that conduct either heat or cold through the wall out into the environment or from the environment back in. It takes an insulated covering that wraps not only up and down the walls and around the roof, but down in front of the foundation wall and under the footing, so the footing doesn't touch the earth. It's sitting on insulation. The entire house is wrapped, which is different than the way most houses are built.

In fact one of the challenges was finding an HVAC system that's small enough to heat and cool this house as it takes so little. We're using a Mini-Split Mitsubishi system, which is the smallest one they make. There's an ERV and 0.6 air changes per hour -- an extremely tight envelope

DCMud: From your paintings it appears there is extensive fenestration, including a huge south-facing exposure with all that this can imply.

Booz: We have high performance windows facing south that offer shading, and an innovative system of translucent exterior roller shades that automatically deploy over these windows to prevent overheating.

DCMud: Interesting you should talk about these key exterior shades, as we did a story with Mark McInturff where they figured prominently into the design.

Booz: The architect who has influenced me most strongly is Mark McInturff, under whom I worked for nearly six years. His language is contemporary architecture and he has a wonderful sense of design. His buildings are light-filled and sustainable, and also very beautiful -- he has a wonderful sense of color and proportion and extreme attention to detail. With his work, the closer you get the better it looks, as opposed to a lot of modern architecture where you get the Gestalt right up front but the closer you look, the more banal it gets.