It’s like walking an ecclesiastical tightrope.

In an effort to renovate centuries-old or even mid-century churches with 21st century acumen, practitioners of the art have learned to strike a delicate balance between old and new, sacred and sustainable. The journey from what was and is, to what needs to be, is often complicated: the act of mixing preservation with practicality a sort of alchemy at which even Harry Potter might marvel.

“With existing buildings of this kind, the important thing to remember is that they have an enormous amount of embodied energy,” said

Hartman-Cox Architects Partner Mary Katherine Lanzillotta, whose D.C.-based firm is responsible for such projects as St. Patrick’s Episcopal Church School, McLean, Va.’s Immanuel Presbyterian Church, and a Duke University Divinity School addition. “The resources that the parishioners put into them from the original construction, both financially and emotionally – for us to keep these buildings active and vibrant is one of the most sustainable things we can do,” she said.

Shepherds of more than 100 church renovations and original construction from New York to Florida, Arlington, Va.-based

Kerns Group Architects Principal Tom Kerns indicated challenges on the church front vary in style and scope. These include building or expanding sacred spaces without forfeiting intimacy, installing air changes to code to eliminate the “sick building” syndrome of 20 years ago and creating spaces that assist young families or entice teenagers to come to worship in the first place.

In this regard, St. Petersburg, Fla.’s First Presbyterian Church – one of the city’s largest –is no different than many houses of worship whose parishioners include overscheduled teens. With school, sports, jobs and other, perhaps less structured attractions vying for young people’s attention, the church, built in the mid-1960s, was without a contemporary space for its youth population to gather. According to Kerns, “The mission of the youth center was to have a place to hang out on Friday nights,” and also to serve as a venue for a Wednesday night praise service and other spiritual activities. Completed three years ago by raising the roof within the existing structure, the two-story assembly space for 150 people boasts LED colored lighting for its performance stage and dances, and a computer lab for homework. A nursery and day school classrooms occupy the bottom floor. “It’s been very successful,” Kerns said.

At Holy Trinity Parish in Georgetown, Washington’s first place of Catholic worship dating back to 1792, an original chapel on a hill built by Bishop Carroll - first bishop of the hierarchy of the U.S. – had become a convent and then a parish office over its 200-year lifespan. A commission to restore the chapel and renovate the entire campus presented a great challenge for Kerns Architects, but one they embraced. “They (the Jesuit community) asked us to restore the chapel and at the same time to express the juxtaposition of this 18th century building with today’s liturgy,” said Kerns, who completed the project about 10 years ago. According to Kerns, exposing the original container – the entire volume – revealed old wooden trusses the architects left as they were. The tower’s interior timber framing was also deliberately exposed, and concealed lighting placed in window sills. With an eye toward additional sustainability, local artisans were engaged to design custom altars, tabernac

les and light fixtures. Campus renovation included staff offices, meeting, and various support spaces. Two courtyards promoted fellowship and facilitated the physically challenged.

“It was a pretty high professional gauntlet to run,” Kerns said, in light of its Georgetown geography. The project took several years and included a year and a half in review, including the Commission of Fine Arts. In the end, much of the 26,000 s.f. project was built below grade to conceal it, which was expensive, but within the framework of a project of this scope.

In 2005 in Durham, N.C., Hartman-Cox’s expansion of Duke Divinity School was an exercise in ecclesiastical efficiency. Duke University was particularly concerned about the site, according to

Hartman-Cox Principal Lee Becker, “with the chapel essentially a small cathedral in Collegiate Gothic style and the campus very cohesive.” Designed by

Horace Trumbauer in 1934 with

Julian Abele as architect/draftsman, the surrounding campus included a 1974 addition “that is a miserable building,” Becker said. A cloister connection piece - the original divinity school - was parallel to the chapel, with an engineering building and library also on site. An approximately 26-foot drop existed between the chapel and the cloister.

“They asked us to fill this in,” Becker said about the drop, “and do something with the cloister.” The building, which is an education building, had to multifunction as classroom and performance space, as well as service and practice space for the choir, requiring acoustical capability. “And it had to have a real ecclesiastical feel,” Becker added. Using Indiana limestone and “Duke stone” for the exterior (Duke has its own local quarry) to match the chapel, a symmetry evolved. “Also, at that time, the university was not seeking LEED certification for buildings,” Becker said, “but it would have qualified.”

According to Hartman-Cox’s Lanzillotta, the LEED certification process is expensive for ecclesiastical buildings and institutions. “When you’re dealing with donor dollars, federal or state dollars, or other forms of fundraising, it may not be the best use of their resources for the documentation,” she said, noting that site selection, mechanical systems, lighting design, drought resistant landscape design, and the envelope – all are sustainable in her firm’s work, with or without certification.

“Architecture is a service profession,” Kerns of Kerns Group Architects said. “They (the churches) hire us to solve a wish list or set of problems." Rather than the quest for LEED certification, “ …what’s at the top is to solve space needs: not enough classrooms or gathering space or accessibility.” Accommodating young families with appropriate facilities or space to grow the music program are their priorities. “But as practicing architects, we’ve been using sustainable ideas for our whole careers,” he said, noting that sometimes more than other clients, churches are more committed to the project and want to be good stewards of the funds they have for their needs or mission.

Duke Divinity School photographs by Bryan Becker.

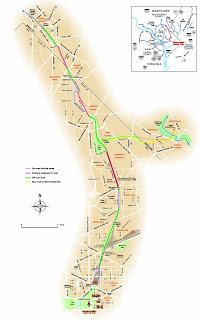

District of Columbia officials opened the newest section of the Metropolitan Branch Trail (MBT) today, a 1.5 mile stretch of pavement that connects Brookland (Franklin Street) to NoMa (New York Avenue).

District of Columbia officials opened the newest section of the Metropolitan Branch Trail (MBT) today, a 1.5 mile stretch of pavement that connects Brookland (Franklin Street) to NoMa (New York Avenue).

In this regard, St. Petersburg, Fla.’s First Presbyterian Church – one of the city’s largest –is no different than many houses of worship whose parishioners include overscheduled teens. With school, sports, jobs and other, perhaps less structured attractions vying for young people’s attention, the church, built in the mid-1960s, was without a contemporary space for its youth population to gather. According to Kerns, “The mission of the youth center was to have a place to hang out on Friday nights,” and also to serve as a venue for a Wednesday night praise service and other spiritual activities. Completed three years ago by raising the roof within the existing structure, the two-story assembly space for 150 people boasts LED colored lighting for its performance stage and dances, and a computer lab for homework. A nursery and day school classrooms occupy the bottom floor. “It’s been very successful,” Kerns said.

In this regard, St. Petersburg, Fla.’s First Presbyterian Church – one of the city’s largest –is no different than many houses of worship whose parishioners include overscheduled teens. With school, sports, jobs and other, perhaps less structured attractions vying for young people’s attention, the church, built in the mid-1960s, was without a contemporary space for its youth population to gather. According to Kerns, “The mission of the youth center was to have a place to hang out on Friday nights,” and also to serve as a venue for a Wednesday night praise service and other spiritual activities. Completed three years ago by raising the roof within the existing structure, the two-story assembly space for 150 people boasts LED colored lighting for its performance stage and dances, and a computer lab for homework. A nursery and day school classrooms occupy the bottom floor. “It’s been very successful,” Kerns said. At Holy Trinity Parish in Georgetown, Washington’s first place of Catholic worship dating back to 1792, an original chapel on a hill built by Bishop Carroll - first bishop of the hierarchy of the U.S. – had become a convent and then a parish office over its 200-year lifespan. A commission to restore the chapel and renovate the entire campus presented a great challenge for Kerns Architects, but one they embraced. “They (the Jesuit community) asked us to restore the chapel and at the same time to express the juxtaposition of this 18th century building with today’s liturgy,” said Kerns, who completed the project about 10 years ago. According to Kerns, exposing the original container – the entire volume – revealed old wooden trusses the architects left as they were. The tower’s interior timber framing was also deliberately exposed, and concealed lighting placed in window sills. With an eye toward additional sustainability, local artisans were engaged to design custom altars, tabernac

At Holy Trinity Parish in Georgetown, Washington’s first place of Catholic worship dating back to 1792, an original chapel on a hill built by Bishop Carroll - first bishop of the hierarchy of the U.S. – had become a convent and then a parish office over its 200-year lifespan. A commission to restore the chapel and renovate the entire campus presented a great challenge for Kerns Architects, but one they embraced. “They (the Jesuit community) asked us to restore the chapel and at the same time to express the juxtaposition of this 18th century building with today’s liturgy,” said Kerns, who completed the project about 10 years ago. According to Kerns, exposing the original container – the entire volume – revealed old wooden trusses the architects left as they were. The tower’s interior timber framing was also deliberately exposed, and concealed lighting placed in window sills. With an eye toward additional sustainability, local artisans were engaged to design custom altars, tabernac